AOS Lecture Notes - Lesson 3 - Virtualization

Introduction to Virtualization

- The drive for extensibility in OS services leads to innovations in the internal structure of OS’s.

- We will cover the concept of virtualization and how it extends the concept of extensibility, allowing the simultaneous coexistence of entire OS’s.

Platform Virtualization

- Goal is to provide a “virtual” platform at a fraction of the cost, by eliding over providing specific hardware.

- Predicated on the assumption that the end user doesn’t generally care how an app is run, so long as it does what the user wants

- amortize cost of ownership, use economies of scale and use patterns to find a lot of margin here.

- However, we as developers care quite a bit.

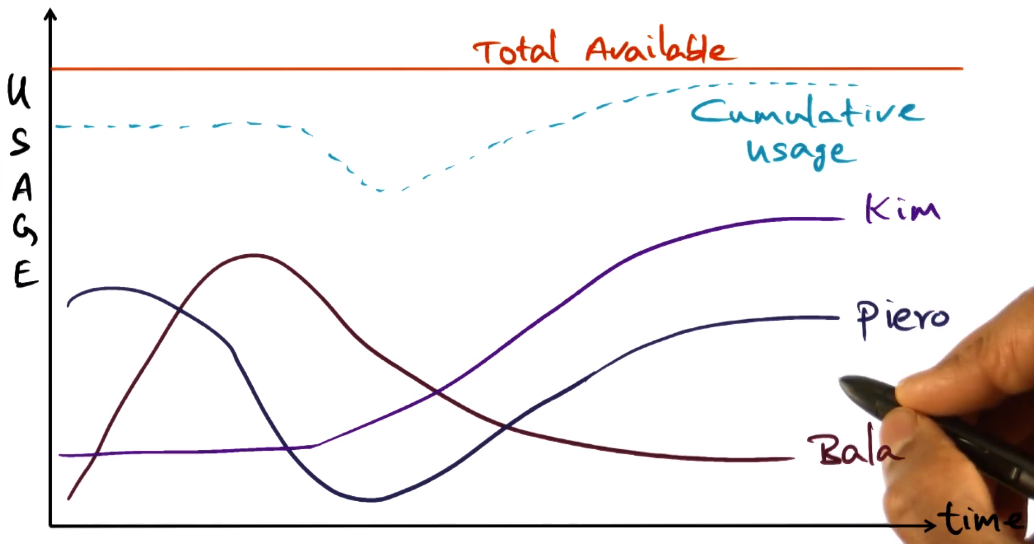

- Key challenge is that usage is usually very bursty

- This means that we need to be mindful of overlaps.

- We need far more resource than the need of any individual platform user.

- However each user then has access to far more resource than they could possibly have afforded on their own

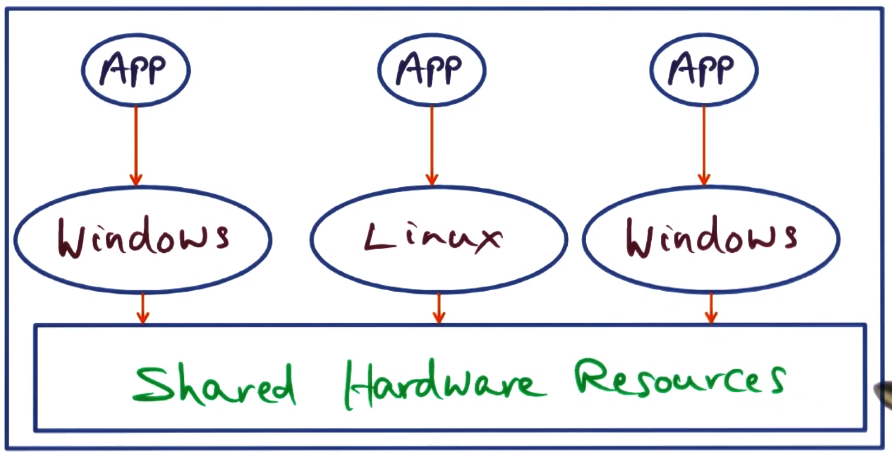

- Virtualization is the concept of extensibility, but applied to an entire OS instead of just the services provided by an OS

Hypervisors

- How do we isolate/protect/run multiple OS’s running on the same hardware?

- What allocates resources? We need an OS of OS’s

- Hypervisor! aka VMM (Virtual Machine Monitor), with OS’s on it referred to as VMs or Guest OS’s

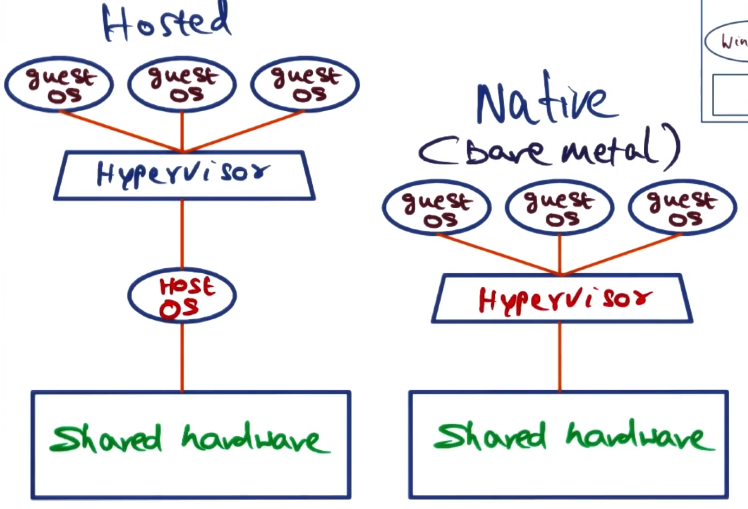

- Two types of hypervisor

- Native (bare metal)

- runs on top of bare hardware

- We’ll focus mostly on these

- interfere minimally with guest OS’s. Similar in philosophy to extensible OS’s

- offer best performance

- Hosted

- runs on top of host OS. Allows users to emulate the functionality of other OS’s

- VMWare Workstation, VirtualBox

- Native (bare metal)

Connecting the Dots

- IBM VM370 (1970’s)

- origin of the concept of Virtualization

- intent was to give the intent to all users that the computer was exclusively theirs

- also to provide binary support for older versions of IBM computers

- Microkernels (late 1980’s and 1990’s)

- Extensibility of OS (1990’s)

- SIMOS (late 1990’s)

- laid the groundwork for the modern resurgence of virtualization tech at the OS level

- Was the basis for VMWare

- Xen + VMWare (early 2000’s)

- proposed originally in the pursuit of supporting application mobility, server consolidation, co-location, distributed web services

- Today – accountability for usage in data centers

- Margin for device making companies is very small. Everyone wants instead to provide “services” for end users

- Companies can now provide resources with complete isolation, and bill users appropriately

- i.e. cloud providers billing app developers who are in turn selling SAAS apps.

Full Virtualization

- The ideal is to leave the guest OS untouched, running exactly as it would itself on bare metal

- Must be a bit clever to manage this, though, as the guest OS’s must still run as user-level processes. The hypervisor must still mediate access to the underlying hardware.

- When guest OS executes privileged instructions, those instructions must trap into hypervisor, which will then emulate the intended functionality of the OS. This is called the trap and emulate strategy.

- Each guest OS thinks it is running on bare metal, and acts accordingly, trying to execute privileged instructions.

- Some privileged instructions may fail silently. Covered in more depth in my GIOS Notes

- Hypervisor will resort to a binary translation strategy

- look for such instructions in guest OS, and through binary editing, ensure that those instructions are dealt with appropriately.

- This has since been fixed for Intel and AMD architectures, where it was a big problem.

- Hypervisor will resort to a binary translation strategy

- Some privileged instructions may fail silently. Covered in more depth in my GIOS Notes

Paravirtualization

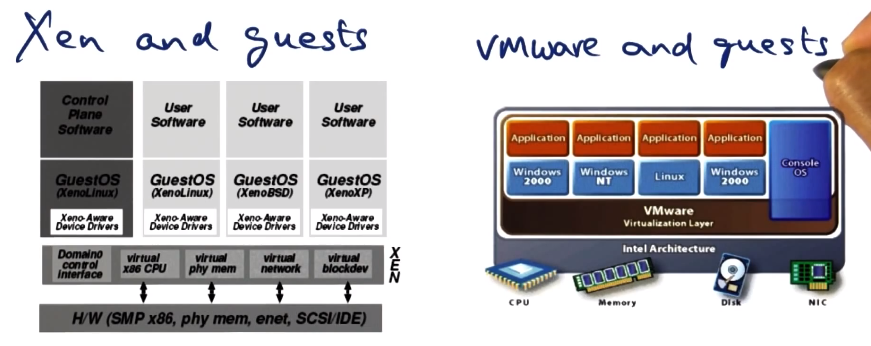

- Not fully virtualized, OS’s know they’re on VMs. Modify the source code of guest OS

- Avoid problematic instructions, and include possible optimizations

- allow guest OS see real hardware resources, employ page coloring, etc.

- No different for the applications running on guest OS, they only know they’re running on whatever OS.

- Xen product family uses this approach.

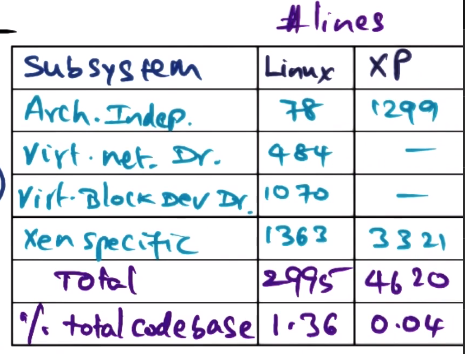

- How much modification is actually needed for guest OS binaries with this approach?

- Xen showed, by proof of construction, that it is less than 2% of the guest OS’s code

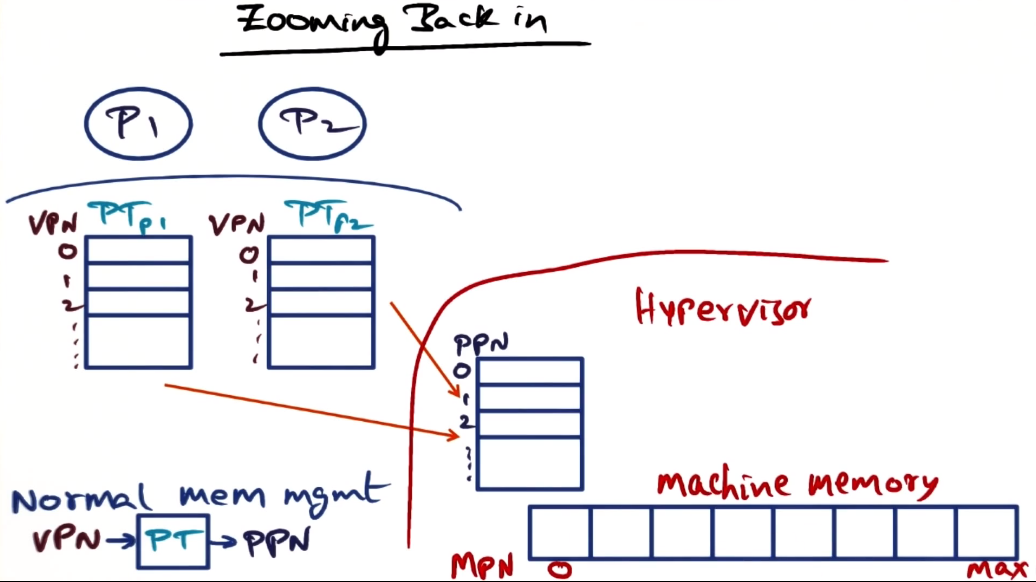

Memory Virtualization

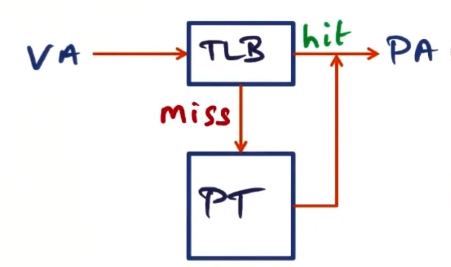

- Stacked viz of memory going rom CPU with TLB down through caches to main memory (RAM) and then to Virtual Memory on disk

- Thorny issue here is handling virtual memory (VA to PA mapping)

- this is the key functionality of the memory management system on any OS

- In any OS each app is in its own protection domain (and usually its own hardware address space)

- Page table holds VA->PA mapping

- Physical memory is contiguous going from 0 to v(Max)

- Virtual address space of a given process is not (does not have to be) contiguous in physical memory (advantage of page-based memory management)

- In full virtualization example, each guest OS process is in its own protection domain

- distinct page table in each guest OS

- does hypervisor know about each page table? no!

- physical memory is thought to be contiguous by guest OS’s, but they don’t actually see physical memory, hypervisor does. and from the hypervisor’s point of view, the memory assigned out to VMs is not contiguous. similar to VA->PA mapping at OS level. terminology used for HV->VM layer is “machine memory” to “physical memory”, for convenience

- Hypervisor maintains its own page table, allocating machine memory out to guest OS’s. Physical page number to machine page number (MPN)

- called the “shadow page table” (SPT)

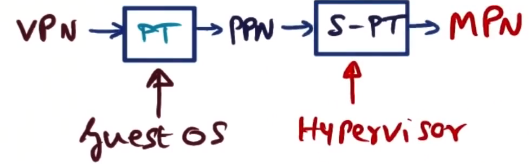

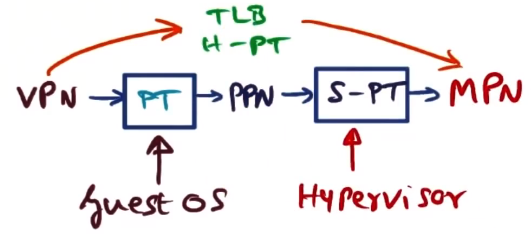

- so all mappings go: VPN->PT->PPN->SPT->MPN

- open question: does guest OS or hypervisor keep the SPT (mapping PPNs to MPNs)?

- in fully virtualized setting, must be kept with hypervisor as there is no guest OS code for handling this process

- in paravirtualized setting, guest OS has been altered to know it is being run in a VM. In this case it can be either, but is usually housed within the guest OS

Efficient Memory Mapping

Fully Virtualized

- in many architectures, CPU uses page table for address translation

- hardware page table is really the SPT in a virtualized setting.

- How to make this efficient?

- two levels of indirection, two lookups, for every mapping is wildly inefficient

- PT/TLB updates of guest OS are privileged, and therefore trapped to hypervisor.

- SPT updated by hypervisor instead.

- as a result, the actual translations are remembered in TLB/hardware PT. we bypass guest OS PT

- This approach is, for example, used by VMWare’s ESX server

Paravirtualized

- Shift the burden to guest OS

- Maintain contiguous “physical memory”

- map to dis-contiguous hardware pages

- More efficient than fully virtualized approach, and possible here because we’re “allowed” to alter the guest OS code.

- Example in Xen:

- provides a set of “hypercalls” for guest OS to use to call to the hypervisor

- Create PT hypercall allows guest OS to allocate and initialize a page frame it has previously acquired from the hypervisor as a hardware resource. It can then target that page frame as a page table data structure directly.

- Switch PT hypercall requesting context switch to new page table from hypervisor.

- Update PT hypercall allows updates in place to page tables on hardware, e.g. as a result of a page fault

- Hypervisor doesn’t need to know details, can just take the requests from guest OS.

- Everything an OS would need to do when running on bare metal must be provided for in this way.

Dynamically Increasing Memory

- How do we increase the amount of physical memory available to a given guest OS?

- Memory requirements tend to be bursty, hypervisor must be able to allocate machine memory on demand

- What happens when guest OS requests memory but host has none to give.

- One option is to claw back some of the memory allocated out to another guest OS that isn’t using it.

- Instead of forced reclamation, a request might be better.

- This concept is called “ballooning”

- the idea is to have a special device driver installed in every guest OS

- Upon needing more memory, hypervisor will contact an under-utilizing guest OS, talking to the balloon driver through private channel.

- Balloon device driver will request memory from guest OS, inflating the balloon and restricting “available” memory visible to guest OS as it pages out to disk other processes’ memory.

- Balloon driver will then return that machine memory back to hypervisor.

- The idea here is that the “balloon” inflates, taking up footprint in the guest OS.

- The reverse of the above, where the hypervisor needs less memory, will deflate the balloon and return that footprint back to “available” status to the guest OS, which will then page in from disk the working sets of whatever processes would like it.

- This model assumes cooperation between the hypervisor and the guest OS, despite the guest OS not actually knowing about the hypervisor. Therefore it is applicable to both fully virtualized and paravirtualized settings.

Sharing Memory Across Virtual Machines

- Can we share memory across VMs without affecting the protection offered to them?

- If two apps have the same data (e.g. two instances of Firefox running on two different VMs), they could in theory share the same PPN.

- The ‘core pages’ of apps are often the same, so this is a common case

- Guest OS has hooks that allow such page frames to be marked copy-on-write on the local page tables on guest OS, and therefore only make copies on machine page table when they diverge

- This requires the guest OS and hypervisor to collaborate

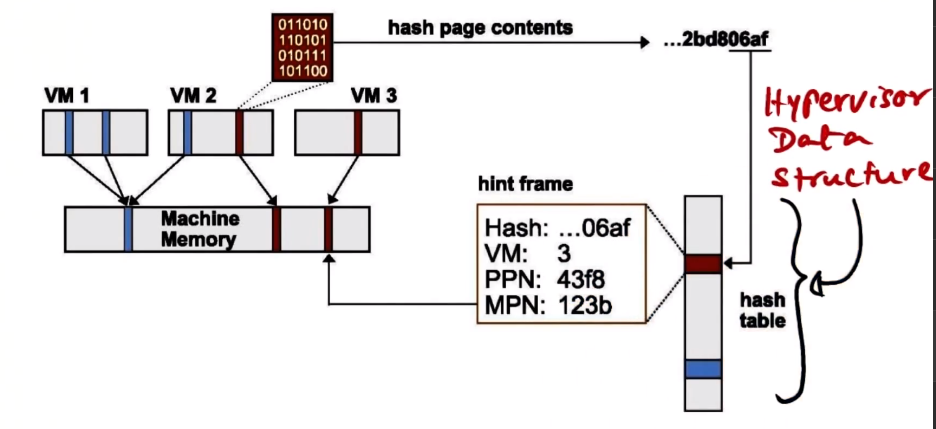

VM Oblivious Page Sharing

- Alternatively, achieve the same effect but without guest OS knowing anything about it

- The idea is to use content-based sharing

- VMWare keeps a hash table in the hypervisor, which contains a content hash of the machine pages.

- To use, hash contents of page table, scan data structure for a match to the hash.

- If you get a match, doesn’t mean it’s for sure match, page may be dirty

- So do a full comparison between page table contents upon match.

- If content matches, map both page tables to same machine page table, increment reference count in hint frame on hash structure. Mark both page tables being mapped to same machine page table as copy-on-write.

- Free up page frame in machine memory, as we have doubled up somewhere else and don’t need it. This is the space savings we’re trying for.

- Scanning pages for such duplicates that we can double up on is done as background activity of the server, when load is low, as these are expensive operations.

- Applicable to both fully virtualized and paravirtualized environments

Summary

- we have discussed mechanism here, but a higher-level issue is policies for how to do all the above.

- The goal of virtualization is maximizing utilization of the virtualized resources

Example Policies

- Pure share based approach (pay less, get less)

- problem is it leads to hoarding. largest share user may not actually need much

- Working-set based approach

- allocation based on actual utilization.

- Dynamic idle-adjusted shares approach

- tax idle pages more than active ones

- determine best tax rate based on your business model or use case, could be 0%, could be 100%, those would be equivalent to the two approaches above

- Reclaim most idle memory (from VMs not actively using it)

- allow for sudden working set increases, as we don’t reclaim all idle memory

CPU and Device Virtualization

CPU Virtualization

- The first challenge challenge here is giving the illusion to guest OS’s that they own the resources

- similar in principle to the illusion provided by OS to apps that they are the only one running on the processor

- Hypervisor must handle program discontinuities, fielded and passed to correct guest OS

- Hypervisor therefore must have precise way of accounting time used on CPU by each guest OS

- Policies for CPU Sharing:

- proportional share

- commensurate with the service agreement that the VM has with the hypervisor

- fair share

- give out equal shares to each guest OS

- In either policy, the hypervisor must account for time used on CPU by one guest during time intended/allocated for another. This might happen due to external interrupts. Recompensing for ‘stolen time’ here.

- proportional share

- The second challenge is delivering events to parent guest OS

- events are generated by process that belongs to guest OS currently executing on CPU

- Once process has been scheduled on CPU, during execution, everything should happen at hardware speeds.

- process will generate virtual addresses that must be translated to machine page addresses (discussed above). This is done at hardware speeds due to techniques above. Very fast.

- process may execute a system call, or a page fault, or an exception, or there may be an unrelated external interrupt.

- these are the discontinuities that may mess with the execution of a process

- all such discontinuities must be passed up to parent guest Os by the hypervisor to be correctly handled.

- events delivered as software interrupts, packaged up by the hypervisor

- the guest OS must then field them and handle as it normally would

- some discontinuities may require the guest OS to have privileged access to CPU (only able to handle in kernel mode)

- this is a problem, especially in fully virtualized environment. guest OS is just user level, but doesn’t know it

- must trap into hypervisor so it can do the work the guest OS would normally have to do

- but some privileged instructions fail silently. noted above, see my GIOS Notes

- as noted, happens in older versions of x86

- in fully virtualized environments, communication between guest OS and hypervisor is always implicit, done via traps.

- in paravirtualized environments, this communication can be explicit, with APIs for communication between the guest OS and hypervisor

Device Virtualization

- here, again, we want to give the illusion to the guest that they “own” the devices

- for full virtualization, we use “trap and emulate” approach

- not a lot of scope for innovation there. must always do what device/OS would do. Lots of finnicky details though.

- for paravirtualization, there is much more opportunity to innovate

- the IO devices seen by guest OS are exactly those available to hypervisor

- can innovate interaction between guest OS and hypervisor here.

- hypervisor can create device abstractions

- hypervisor can expose shared buffers to guest OS, so that data can be passed efficiently between guest OS and hypervisor, and to devices, without overhead of copying between address spaces

- even delivery of data can be innovated

- need to sort out how to transfer control between hypervisor and guest.

- hardware manipulation must still be done by privileged operations

Control Transfer

-

Full Virtualization

- implicit (traps) from guest to hypervisor

- when guest OS executes any privileged instruction it results in a trap. hypervisor catches and does whatever is needed

- in the other direction (hypervisor to guest OS) is done via software interrupts (events)

-

Paravirtualization

- explicit (hypercalls) from guest OS to hypervisor (example in memory section with page faults)

- in the other direction (hypervisor to guest OS) is done via software interrupts (events), similar to full virtualization

- difference from full virtualization is that guest OS has control via hypercalls on when event notifications are delivered

- similar to an OS disabling interrupts

Data Transfer

- In full virtualization environments data transfer must be done implicitly

- In paravirtualized environments (e.g. Xen) it is done explicitly, again giving opportunity to innovate

- two aspects to resource management and accountability

- CPU Time (time issue)

- when an interrupt comes in, hypervisor has to de-multiplex the data coming from device to domains very quickly.

- this takes CPU time to do, and the hypervisor must account for computation time for managing buffers on behalf of the guest OS above it

- this is especially important in the context of e.g. a data center, where you must bill appropriate VMs for their usage

- How the memory buffers are managed (space issue)

- how are these allocated and managed either by guest OS or by hypervisor?

- Xen’s async I/O rings

- a data structure shared between guest and Xen

- any number of I/O rings can be allocated for handling all device I/O needs of a particular guest domain

- the I/O ring itself is just a set of descriptors

- idea is that requests from guest can be placed in I/O ring by populating the descriptors.

- every request will have a unique ID

- I/O ring is specific to a guest

- after hypervisor completes processing a request, it will place a response back in the same I/O ring in one of the descriptors. this response will have the same ID as the original request.

- symmetric relationship between guest and Xen in terms of request and response

- guest is producer of requests. has a pointer into the ring that indicates where to place next request. pointer is modified by guest, but readable by Xen

- Xen is consumer of requests. it consumes requests in the order the guest produced them. it has a pointer into the ring that indicates where it is presently servicing requests. This pointer is private to Xen.

- Difference between guest’s request pointer and Xen’s request pointer tells Xen how many outstanding requests there are for Xen to service.

- Xen has a second pointer for producing responses. This pointer is modified by Xen, readable by guest.

- Guest OS has a second pointer for consuming responses. This pointer is private to the guest.

- Difference between Xen’s response pointer and guest’s response pointer tells guest how many outstanding responses there are for guest to process.

- Empty slots are theoretically available between request and response sections as all four pointers progress.

- Remember, ring just has descriptors. These must have pointers to machine pages where the data actually resides.

- CPU Time (time issue)

- two aspects to resource management and accountability

- Network virtualization in Xen example

- each guest has two I/O rings, one for transmission and one for reception

- if guest wants to transmit packets, it enqueues descriptors in transmit ring, via hypercalls

- packets that need to be transmitted are in guest OS buffers. guest embeds pointers to these buffers in descriptors in ring. data is not copied.

- pages associated with the packets are pinned so that Xen can complete transmission of the packets

- if more than one guest OS wants to transmit, Xen uses a round robin scheduler to transmit packets from multiple VMs

- Receiving packets from network and passing to appropriate domain works the same, but in opposite direction.

- hypervisor exchanges received packet for one of the guest OS pages that has been provided to Xen as the holding place for incoming packets.

- guest OS pre-allocates network buffers for this purpose. Xen places directly there, and enqueues a descriptor. avoids copying

- if Xen receives a packet into a machine page instead, it can just swap with a page the guest OS owns, avoiding copying that way instead.

- Disk I/O Virtualization example

- works similarly to network virtualization example

- Every VM has an I/O ring dedicated to disk I/O

- communication between Xen and guest OS avoids copying, enqueues descriptors with pointers

- philosophy is asynchronous I/O via requests/responses.

- Requests from competing domains may be reordered

- if this is inappropriate, Xen provides a reorder barrier for guest OS semantics, to prevent this from happening if needed.

Usage and Billing

- all about measuring time

- The whole tenet is that we’re sharing resources between clients. Need to be able to measure them

- CPU Usage

- Memory Usage

- Storage Usage

- Network Usage

- Xen vs VMWare - and Guests

- Difference from Extensible OS is a strong focus on protection and flexibility, with sharing at full OS level